As governors grapple with the question of when to reopen their states, the need for a well-organised, wide-scale contact tracing effort is at the top of many experts’ lists.

Rival tech giants Google and Apple announced a collaborative plan that would use smart phones to aid in the effort, and Apple CEO Tim Cook says the first draft of their effort would be working by next Tuesday. But the plan raises questions about effectiveness — and data privacy.

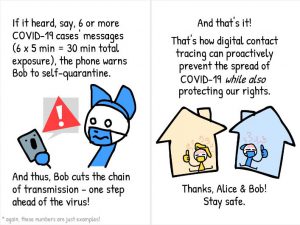

The companies’ API would provide a way to pinpoint users who had been within 6 feet of an individual diagnosed with COVID-19. Those users could then quarantine themselves and watch for any symptoms of the virus.

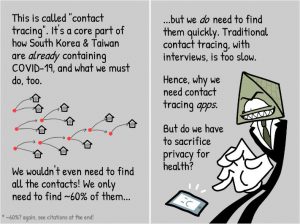

But in order for that to effectively slow the spread of the virus, at least 60% of smartphone users would have to agree to participate in the initiative.

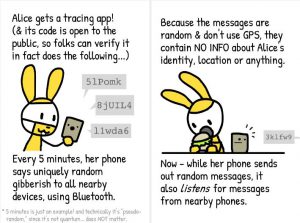

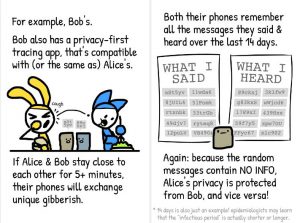

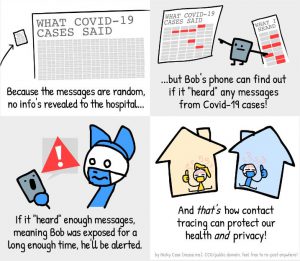

Traditional contact tracing methods are potentially as slow as detective work, and prone to the fallibility of human memory. This method was designed with technology and privacy in mind. It uses Bluetooth, the wireless technology which connects phones to speakers and other smart devices, and does not rely on GPS or individual’s phone numbers.

Derek Eder, founder of DataMade, a civic technology company, and co-founder of Chi Hack Night, is concerned first and foremost about privacy.

“Great care needs to be taken to ensure the scope and data sharing partners are limited. Technology is unfortunately often seen as a ‘silver bullet’ for intractable problems. The reality is it still requires a lot of hands on work with existing methods, which technology can amplify, to get it done effectively,” he said.

It also leaves out potentially billons of people on the planet. Any android device used in China, where the virus originated, does not even accept Google operating systems.

Blase Ur, University of Chicago associate professor of computer science, points to a recent article at Forbes.com that determines nearly 2.5 billion cellphone users would not be able to use the technology.

“If the hardware, and even the software, is not up to date or compatible it won’t be possible to use the API,” he said. “And there is a very real correlation between the most vulnerable and those whose devices won’t be able to access this.”

Ur notes that all one has to do is imagine the people they know in their family who aren’t using smartphones, and in many cases it is the older generation, who also happen to be particularly susceptible to the virus.

In Chicago, where some African Americans communities are seeing disproportionately high rates of infection and death related to COVID-19, there are worrying numbers about access as well.

Eder points to out that 15% of households in Cook County, a little under 300,000 households, do not have smartphones.

“The people in that 15% are likely to be at greater risk of contracting and dying from COVID-19. This is not to say the initiative is bad — but we also need to think about who it is not able to reach. The future is here, as we like to say, but it isn’t evenly distributed,” he said.

An even bigger question is when the system, if it goes into use, gets turned off. And who gets to turn it off.

“The government has been way behind on oversight of these firms,” Eder said. “And they are very resistant to anyone checking their work.”

US adds that it will be hard to resist the urge to re-purpose the system afterwards. “Will they say, ‘Oh well, it wasn’t so bad, why don’t we use it for advertising too?’ Once you build an infrastructure, it is not so easy to resist.”

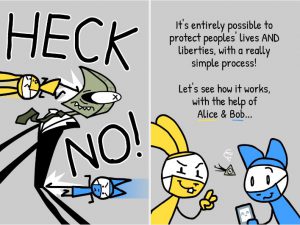

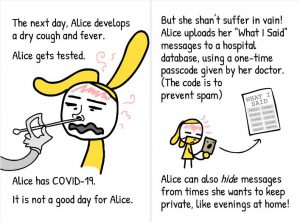

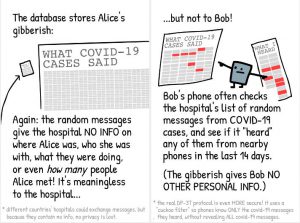

A comic strip being widely shared by the two firms explains the details in a clever way.

\